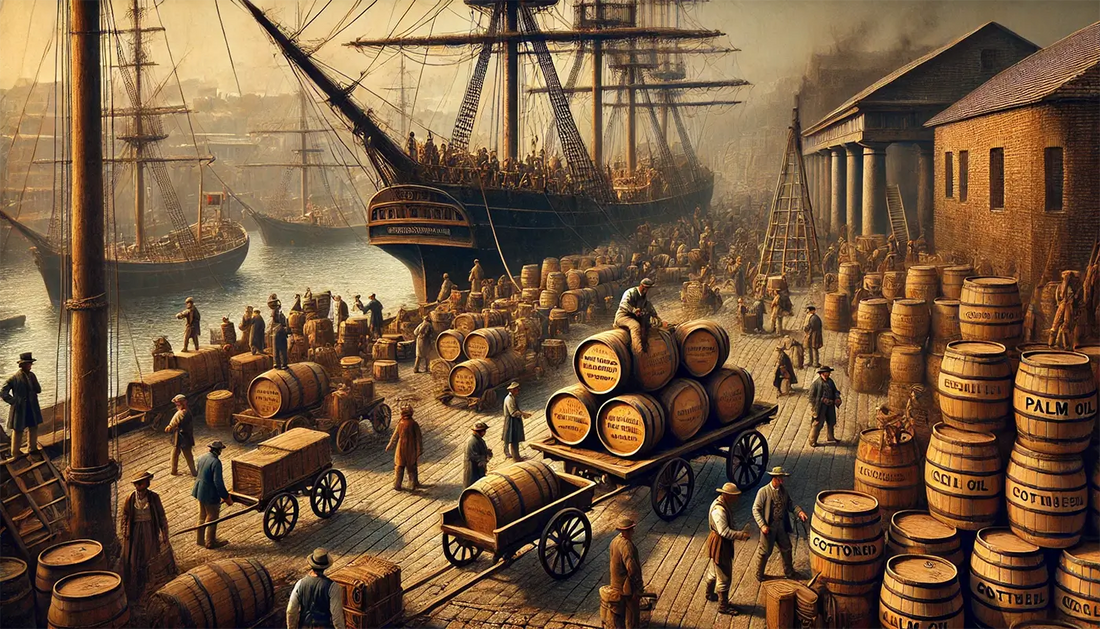

How British imports of non-traditional oils transformed India’s culinary and economic landscape

India’s rich culinary traditions have long been rooted in its indigenous oils like sesame, coconut, and mustard oil. These oils were not just cooking mediums but also cultural cornerstones and Ayurvedic staples. However, British colonization disrupted this ecosystem by introducing non-traditional oils, industrialized production methods, and policies that prioritized their commercial interests. These changes significantly altered India’s culinary and economic landscape, with impacts that continue to reverberate today.

British non-traditional oils and the decline of traditional Indian oils

India has historically relied on cold-pressed oils, extracted using ghanis (traditional wooden presses). These oils were nutrient-rich and deeply connected to India’s food and health traditions. Oils like sesame, groundnut, coconut, and mustard were staples, valued for their flavour, aroma, and medicinal properties.

The British arrival marked the decline of these oils. They introduced industrial expeller machines designed for large-scale oil extraction. These machines prioritized quantity over quality, stripping oils of their natural nutrients. As a result, traditional oil producers and small-scale ghanis were displaced, and the local economy began to crumble.

Key factors behind the decline

- Promotion of industrialized oil mills: The British actively promoted industrialized expeller machines. These machines could produce oil faster and in larger quantities than traditional ghanis. While this suited their economic goals, it compromised the quality of the oils. Traditional methods, which preserved the natural flavour and nutritional value of oils, became less viable. Local producers could not compete with the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of industrial mills, leading to the widespread closure of traditional oil mills.

- Monopoly of cash crops: The colonial administration prioritized cash crops like cotton, jute, and indigo over oilseeds. This focus disrupted India’s agricultural economy. Farmers were pushed to grow crops that served British industrial needs, reducing the cultivation of oilseeds like sesame, groundnut, and coconut. This decline in oilseed production directly impacted the availability and affordability of traditional oils.

- Import of cheaper oils: Cheaper, industrially processed oils like palm oil were imported from British colonies in Africa and Southeast Asia, particularly Malaysia and Indonesia. These oils flooded Indian markets and were marketed as economical alternatives to traditional oils. Local oil producers, unable to compete with these low-cost imports, suffered massive losses. The widespread availability of imported oils further marginalized traditional oils.

- Taxation policies: British taxation policies were heavily skewed against traditional oil production. High taxes and tariffs made it financially unsustainable for small-scale oil producers to continue their trade. At the same time, industries using expeller machines or importing raw materials received incentives. This dual policy accelerated the decline of traditional oil production and boosted industrial oil mills.

- Cultural disruption: The British promoted the idea of modernization in food habits, often branding traditional practices as outdated or inferior. Traditional oils, deeply tied to Ayurveda and Indian culinary practices, were sidelined in favour of industrially processed oils. This shift not only affected dietary habits but also eroded the cultural significance of oils like sesame and mustard.

- Suppression of local industries: Traditional oil mills were typically run by small, community-based producers. These mills were more than just economic units; they were integral to the social fabric of rural India. British policies, aimed at centralizing production and revenue generation, led to the dismantling of these local industries. Millions of artisans and farmers who depended on these mills lost their livelihoods.

- Environmental impact: The British emphasis on monoculture farming and synthetic fertilizers further exacerbated the decline of oilseeds. This approach depleted soil quality and reduced the yields of traditional crops. The environmental impact of these policies continues to affect Indian agriculture.

- Transition to industrialized oils post-independence: Even after independence, the colonial legacy of industrialized oil production persisted. India inherited an economy structured around large-scale industrial units. Traditional oils remained marginalized, as refined, industrially processed oils dominated the market.

Non-traditional oils imported into India

The British brought various non-traditional oils into India, which significantly altered the country’s oil consumption patterns.

Palm oil: Palm oil was imported from British colonies in Africa and Southeast Asia, such as Malaysia and Indonesia. It was cheap and industrially processed, making it accessible to the masses. However, palm oil lacked the flavour, aroma, and medicinal properties of traditional Indian oils. Its widespread availability diminished the demand for oils like coconut and sesame.

Cottonseed oil: A by-product of the cotton industry, cottonseed oil was introduced as an alternative edible oil. The British promoted its use because it was cost-effective and easy to produce in industrial mills. However, its introduction overshadowed small-scale traditional oil producers, further marginalizing their trade.

Soybean oil: Soybean oil entered the Indian market from Western nations, particularly the United States. Refined and mass-produced, it was marketed as modern and versatile. However, it clashed with Indian culinary practices, which relied on oils that added flavour and complemented traditional cooking styles.

Rapeseed/Canola oil: Rapeseed oil, later refined into canola oil, was imported for its efficiency in large-scale production. It displaced mustard oil, a staple in northern Indian diets. The replacement not only affected cooking practices but also disrupted cultural and medicinal traditions tied to mustard oil.

Sunflower oil: Introduced during the colonial era, sunflower oil was brought from Europe. Its neutral flavour and affordability made it popular, but it lacked the nutritional richness and cultural relevance of traditional Indian oils.

Corn oil (Maize oil): Corn oil, a by-product of maize cultivation, was affordable and industrially processed. While it gained traction for its low cost, it could not rival traditional oils in flavour or health benefits.

Linseed oil: Primarily imported for industrial uses like varnish production, linseed oil occasionally made its way into the edible oil sector. Its limited culinary applications added to the competition traditional oils faced.

British non-traditional oils and its impact on India’s culinary practices

The introduction of non-traditional oils had a profound effect on Indian cooking. These oils lacked the distinct flavour and aroma of traditional oils. Their refinement processes stripped them of natural nutrients, making them less healthy.

Traditional oils like mustard, sesame, and coconut were deeply tied to Ayurveda. They were known for their medicinal properties and were integral to Indian dietary practices. The replacement of these oils with imported alternatives disrupted this harmony.

British imports of oils: Economic consequences for India

The decline of traditional oils also had severe economic implications. Farmers growing oilseeds faced declining demand, leading to economic instability. Artisans operating ghanis lost their livelihoods as industrial oil mills took over.

The British policies, which prioritized centralized industrial production, undermined India’s rural economy. The dismantling of small-scale industries created a gap that persists even today.

British imports of oils: Environmental impacts

The environmental impact of the British policies cannot be ignored. Monoculture farming and the use of synthetic fertilizers degraded soil quality. This not only reduced the yields of oilseeds but also affected the sustainability of Indian agriculture.

British non-traditional oils and its long-term implications

The reliance on industrially processed oils introduced during British rule continues to affect India. These oils, often refined and adulterated, are less healthy than traditional cold-pressed oils.

Reviving traditional oils is not just about reclaiming cultural heritage. It also involves addressing their health benefits and promoting sustainable agricultural practices.

Conclusion

The British colonization of India reshaped its oil industry, leaving a legacy that persists to this day. By introducing non-traditional oils and promoting industrialized production, they disrupted India’s culinary, economic, and cultural systems.

To reverse this trend, India must focus on reviving traditional oils, supporting local economies, and promoting sustainable practices. The rich heritage of oils like sesame, coconut, and mustard deserves to be preserved for future generations.

Bibliography

- Stein, B. (1992). The Making of agrarian policy in British India, 1770-1900. Oxford University Press.

- Kumar, N. (2016). Economic Impact of British Colonial Rule on Indian Agriculture: A Review. International Research Journal of Social Sciences.

- Jones, G. (2015). The State and Economic Development in India 1890–1947: The Case of Oil. Modern Asian Studies.

- Roy, T. (2015). The Economic Legacies of Colonial Rule in India: Another Look. Economic and Political Weekly.

- Jain, S. (2020). Building 'Oil' in British India: a Category, an Infrastructure. Journal of Energy History.

Image Courtesy: ACCENTERRA

Did you find this blog post helpful? Got ideas or questions? Join the conversation below! Your insights could help others too, so don’t hesitate to share!

Please note that all comments will be moderated before being published.